TRANSLATIONAL & BASIC CILIARY CELLULAR BIOLOGY

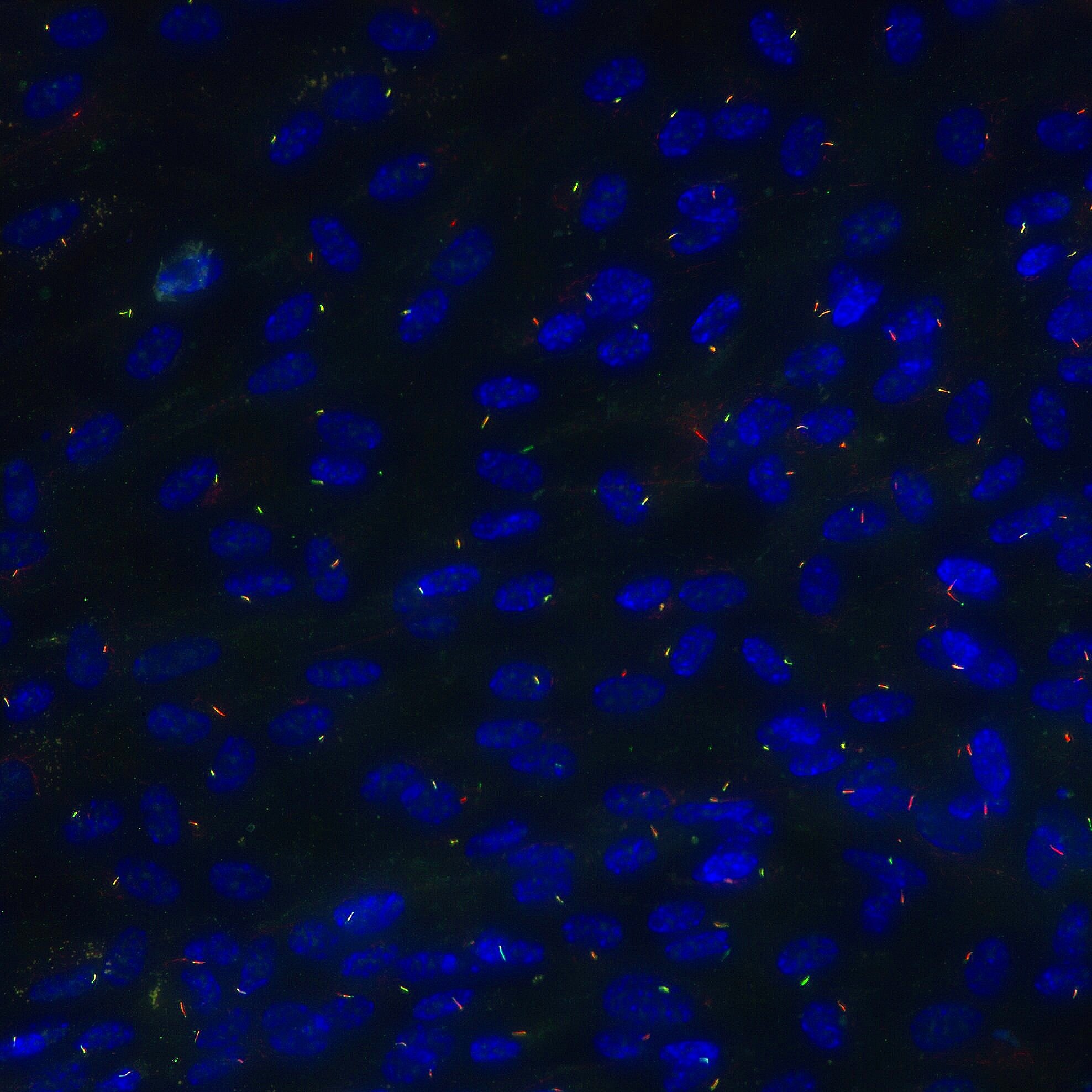

OUR LAB AIMS TO UNDERSTAND HOW CILIA WORK THROUGH THE LENS OF CELL BIOLOGY AND HUMAN GENETICS.

We interrogate ciliary protein function, their dysfunction due to disease-related DNA changes, and their roles in normal and pathological states. Too many parts of this intricate cellular machine fall within the ‘ignorome,’ limiting our comprehensive understanding of this organelle. We use understudied, disease-related proteins to illuminate fundamentals of cilia biology.

We work with human cells and the biciliated green algae, Chlamydomonas. By using both models, we can dissect protein function with greater depth and flexibility.